How To Enjoy a Horror Movie Remake

But I'm the Best!

It seems like we read about them on a daily basis: yet another announcement of a shiny new remake of yet another horror movie classic that we either grew up loving or learned to love from someone older than us who grew up loving it. Child’s Play, Pet Sematary, It, Ghostbusters, and even marginal classics like Flatliners have all suffered the consequences of the horror movie remake frenzy and subsequent backlash. Some films, such as Cabin Fever, hadn’t even been around long enough for many to consider them classics before being shredded into remake fodder.

So, the announcement is made, and immediately thereafter comes the social media hate. It doesn’t take long before someone out there demands that the remake producers not “ruin my childhood,” or that there’s no creativity left in Hollywood, or that producers do little more these days than chase the almighty dollar. I’ll admit, when the remake of Fright Night was released back in 2011, I was one of those cranky old bastards who swore he’d never watch it because of my undying love and respect for writer/director Tom Holland’s original 1985 film.

So, the announcement is made, and immediately thereafter comes the social media hate. It doesn’t take long before someone out there demands that the remake producers not “ruin my childhood,” or that there’s no creativity left in Hollywood, or that producers do little more these days than chase the almighty dollar. I’ll admit, when the remake of Fright Night was released back in 2011, I was one of those cranky old bastards who swore he’d never watch it because of my undying love and respect for writer/director Tom Holland’s original 1985 film.

[the_ad id=”1180″]

Then, one day a few years after the remake was released, I actually sat down and watched it. I don’t know what compelled me to do so. I set aside my preconceived notions and determined that I was going to sit and watch this Colin Farrell/Anton Yelchin/David Tennant outing as if I had never laid eyes on the 1985 version. To my surprise–my very great surprise–I didn’t hate it. The 2011 version of Fright Night contained a solid story, solid acting by professionals, awesome technical execution, and some wonderful surprises. Yes, I will always love the 1985 Fright Night. No, I’ll probably never feel the same way about the remake. But…I found the 2011 version watchable and I no longer feel an enraged desire to tear apart any mention of it, nor even bother to compare it to the original.

Why?

Because I put aside my personal feelings about the original and decided to judge the remake on its own merits and as its own product. My childhood memories are not tied exclusively to my love for the 1985 Fright Night. And, believe it or not, time and space are not so finite as to wink one version out of existence so that another can take its place in cultural memory. They can both exist! At the same time and in the same universe and without consequence one to the other!

Because I put aside my personal feelings about the original and decided to judge the remake on its own merits and as its own product. My childhood memories are not tied exclusively to my love for the 1985 Fright Night. And, believe it or not, time and space are not so finite as to wink one version out of existence so that another can take its place in cultural memory. They can both exist! At the same time and in the same universe and without consequence one to the other!

Heresy, you say? I’ll make it worse for you: I also like the Mick Garris/Stephen King miniseries adaptation of King’s novel The Shining. It tells the story much closer to the way King envisions it in the novel. I simultaneously love Kubrick’s adaptation, which I feel is much creepier and much more artsy than the miniseries, but does not actually tell the story. Here’s another shocker: I prefer the remake of The Last House on the Left far and above the original, even though the original was written and directed by horror icon Wes Craven.

[the_ad id=”1180″]

Now that you’re foaming at the mouth over my audacity to actually like a film that is neither an original nor an original adaptation of other source material, I’m going to offer you some advice to help you get over your own remake-loathing malady. First, soothe yourself by not caring so much about shit like this. Film is both art and entertainment, but it is not the fabric that holds your world together. If your blood pressure spikes because someone has announced a remake of a film that you love, consider that you might be too emotionally invested in that original and try to step back from it a pace or two. Outrage over a movie is not worth putting yourself in the hospital.

Next, I’ll give you a few facts that you can chew on that might help put your remake outrage into perspective.

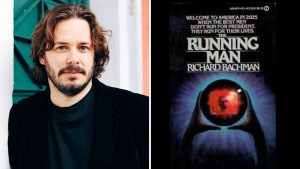

Not every new adaptation of a source material is actually a remake of a classic film. In fact, I would argue that any film that is adapted from source material other than a previous film is not a remake of a previous film. That goes for 2019’s Pet Sematary, 2017 and 2019’s It, and the miniseries adaptation of Stephen King’s The Shining. None of those films are remakes of previous adaptations. They are, instead, new adaptations of Stephen King’s original source material. Think about it: does anyone ever consider a new Dracula film a remake of an older Dracula film? How about Dickens’ A Christmas Carol? Nope. There’s an easy way to identify these non-remakes. Look at the opening title sequences. If they say, “Based on the novel/short story/toilet paper doodle/phone pad scribbling by Stephen King,” the film is not a remake. It is a new adaptation. Frankly, King is probably headed for Shakespeare-level re-adaptation and re-imaginings once his time on Earth is no more. Expect another new Pet Sematary or It adaptation some thirty years from now.

Not every new adaptation of a source material is actually a remake of a classic film. In fact, I would argue that any film that is adapted from source material other than a previous film is not a remake of a previous film. That goes for 2019’s Pet Sematary, 2017 and 2019’s It, and the miniseries adaptation of Stephen King’s The Shining. None of those films are remakes of previous adaptations. They are, instead, new adaptations of Stephen King’s original source material. Think about it: does anyone ever consider a new Dracula film a remake of an older Dracula film? How about Dickens’ A Christmas Carol? Nope. There’s an easy way to identify these non-remakes. Look at the opening title sequences. If they say, “Based on the novel/short story/toilet paper doodle/phone pad scribbling by Stephen King,” the film is not a remake. It is a new adaptation. Frankly, King is probably headed for Shakespeare-level re-adaptation and re-imaginings once his time on Earth is no more. Expect another new Pet Sematary or It adaptation some thirty years from now. The idea that there’s no creativity or original ideas left in horror movie making is easily debunked by one name: Jordan Peele. Both Get Out and Us are original Peele works, not even adapted from non-film source material. Peele is the most obvious answer to the “no more original ideas” argument, but he is far from the only one. There’s also La Llorona, which is based on an urban legend but is still perfectly new and original, Velvet Buzzsaw, Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark (based on a book source and folktales), Doctor Sleep, Castle Rock, and so much more.

The idea that there’s no creativity or original ideas left in horror movie making is easily debunked by one name: Jordan Peele. Both Get Out and Us are original Peele works, not even adapted from non-film source material. Peele is the most obvious answer to the “no more original ideas” argument, but he is far from the only one. There’s also La Llorona, which is based on an urban legend but is still perfectly new and original, Velvet Buzzsaw, Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark (based on a book source and folktales), Doctor Sleep, Castle Rock, and so much more.- Finally, remakes, re-imaginings, and reinterpretations of classic horror movies do not erase the classics. All you need to do is tune into Shudder TV on Friday nights and watch Joe Bob Briggs’ The Last Drive-In to understand that remakes are not necessarily replacements. Joe Bob aired the original The Texas Chainsaw Massacre during his Dinners of Death marathon even though a 2013 remake, which Darcy the Mail Girl prefers over the original, exists. The 2011 remake of The Thing has neither erased the 1982 John Carpenter classic The Thing nor has it erased the original original The Thing From Another World on which Carpenter based his remake.

I wonder sometimes whether our modern inability to accept differing opinions on anything from politics to art to entertainment is to blame for the hyperbolic heart attacks that the announcements of remakes appears to cause on social media. Maybe if we all relearn that it’s perfectly fine to like the 2013 Texas Chainsaw Massacre, or to even (heresy!) prefer it over the original, the world will be a better place.

So, in my humble opinion and regardless of what you think dear reader, here’s to a future of new horror and new adaptations of old horror.

So, in my humble opinion and regardless of what you think dear reader, here’s to a future of new horror and new adaptations of old horror.

Full disclosure: I have not seen the 2013 remake of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.